A la caza de Joseph Kony jefe del Ejército de Resistencia del Señor

2 participantes

Página 1 de 1.

A la caza de Joseph Kony jefe del Ejército de Resistencia del Señor

A la caza de Joseph Kony jefe del Ejército de Resistencia del Señor

‘Small footprint, high payoff’: US Marine team trains Ugandan forces to face al-Shabaab, LRA

3/14/2012 By Cpl. Jad Sleiman , Marine Forces Reserve

KAMPALA, Uganda — A thousand miles from the nearest major American base, about 30 U.S. Marines have been training a company of Ugandan soldiers for the fight against terrorism in East Africa since arriving in country, Feb. 3.

Special Purpose Marine Air Ground Task Force 12, the Marines’ Sicily-based parent command, is tasked with sending small training groups into Africa to partner with local militaries in an effort to indirectly blunt the spread of extremist groups across the continent.

The Uganda team of force reconnaissance, infantry, and combat engineering Marines first covered the use of a variety of weapons systems, marksmanship and field medicine, common soldiering skills Ugandan leaders say their men can use against the brutal Lord’s Resistance Army. More specialized follow on training began March 5 and is designed to help the Ugandan field engineers counter al-Shabaab insurgency tactics in Somalia, where urban obstacles and IEDs reminiscent of the war in Iraq are common.

“We are answering a stated need by our African partners,” said Lt. Col. David L. Morgan, commander of SPMAGTF-12 and 4th Force Reconnaissance Company. “Our mission in Uganda is yet another example of what this versatile force can do.”

The task force has dispatched teams across a wide swath of Africa over the course of their six month deployment in support of Marine Forces Africa, sending anywhere from five to 50 Marines into partner nations for days to months at a time. The unit is among the first of its kind and the mission in Uganda is one of its last.

From al-Shabaab to the LRA

“The soldiers on training will use the acquired knowledge in war-torn Somalia and in the hunt down of fugitive LRA commander Joseph Kony wherever he is,” said Ugandan People’s Defense Force Lt. Col. Richard C. Wakayinja, a senior officer in the field engineering unit training with the Marines.

The UPDF is simultaneously providing the bulk of the more than 9,000 African Union peacekeepers engaging al-Shabab in Somalia while also staying on the hunt for Kony and his militia as they skirt the dense wilderness of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and South Sudan.

Their membership estimated to be in the hundreds, the cultist LRA is condemned by international human rights groups for a lengthy list of atrocities that includes mutilating living victims and forcing children into their ranks as either soldiers or sex slaves. The Obama administration ordered 100 combat advisers into central Africa last fall to aid in the hunt for their elusive Ugandan leader.

Al-Shabaab, which officially became a part of al-Qaida’s terrorist network in February, claims responsibility for the 2010 twin bombings in Kampala that killed 74 as they watched a World Cup final on television. The group also banned foreign aid agencies from Somalia as drought and famine ravaged the region last year.

Mogadishu-specific segments of training are scheduled to go over common combat engineering skills used to harden occupied urban spaces against complex attacks involving dangers like sniper and rocket fire as well as how to blast through enemy obstacles and difficult terrain. Another major focus will be on how to find IEDs before friendly forces get too close, said US Marine Maj. Charles Baker, the mission officer in charge.

“We’ve got force reconnaissance and engineers here together, that gives you the route reconnaissance skills,” he said, adding that the U.S. government would provide the UPDF with engineering equipment and vehicles worth about $8 million.

Shifting to a smaller footprint

U.S. military officials say mission’s like SPMAGTF-12’s could become more common place as troop levels in Afghanistan drop in line with an approaching 2014 combat mission end date. The 180-strong unit was formed over the summer of 2011 from Marine Forces Reserve units based across the country and equipped with two KC-130 Hercules aircraft to ferry teams to and from African countries.

“Because of the past ten years, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, there haven’t been a lot of forces available for Africa,” said Army Maj. Jason B. Nicholson, Chief of the Office of Security Cooperation at the U.S. Embassy in Kampala and former Tanzania foreign area officer.

SPMAGTF-12 has so far sent small teams into five African nations, including some threatened by a North African franchise of Al Qaeda attempting to spread its influence known as al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb or AQIM. The small task force team working with the UPDF represents one of the first significant security cooperation missions undertaken by the DoD in Uganda, a nation more accustomed to State Department interaction.

Undersecretary of the Navy Robert O. Work singled out the task force as a prime example of the type of “low footprint, high payoff operations” the White House is seeking as a means of maintaining global defense postures as the Pentagon pledges to cut at least $450 billion in defense spending over the next decade. The Corps is slated to reduce its active-duty troop strength from the current 202,000 to 182,100, leaving the force with about 7,000 more Marines than it carried before 9/11. In Uganda and Africa in general, US officials say, less can still be more.

A smaller U.S. force has the flexibility to move quickly, such as when a Djiboutian motor pool requested the task force’s help while preparing to deploy their first units to Mogadishu only weeks before their departure date last December. Using a small group like the one in Uganda, said Nicolson, can also simplify the complex politics associated with deploying and hosting troops in a foreign nation. Army Gen. Carter Ham noted African nations’ reluctance to host large numbers of U.S. troops as one reason for U.S. Africa Command’s headquarters to remain in Europe despite growing threats in Africa during testimony to Congress, Feb. 29.

The speed and maneuverability of slender teams, however, comes at a cost. As they partner with the UPDF, the Marines’ closest major source of U.S. support is Camp Lemonnier near Djibouti City, Djibouti. They and other task force teams operate, as unit leadership say, “alone and unafraid,” leveraging their needs against local resources and the limited supplies they can bring with them.

“We’ve grown used to operating near a base that can supply us with what we need,” said Gunnery Sgt. Brian Rivero, staff non-commissioned officer in charge of the mission. “Down here we’ve had to rely on the Ugandan economy for everything from food and water to medical care.”

The task force is built around 4th Force Reconnaissance Company, based in Alameda, Calif. The special operations capable unit is suited for what’s called “deep recon,” whereby teams operate well behind enemy lines with little to no support. Their Uganda partnership is strictly a train and equip mission designed to allow the UPDF, widely considered one of the most professional militaries in the region, to stay on the lead. The Marines in Uganda are working on friendly turf far from hostile fire, but remain very much on their own.

“The complexity of this endeavor cannot be understated,” said Morgan. “Despite the logistical challenges associated with acquiring the necessary ammunition and equipment for Ugandan forces, and complexities associated with operating in Africa, the men and women of the SPMAGTF have endured and created a superior program and partnership.”

Future expeditions

Marine leadership have grown to fear the specter of the Corps becoming a “second land Army” with dwindling relevance after more than a decade of static fighting in the Middle East. SPMAGTF-12’s missions on the continent could represent an early example of a long heralded Marine Corps return to globetrotting, quick reaction operations.

Already, a separate Marine Air Ground Task Force is planned for the Asia-Pacific region with troops basing in Darwin, Australia. The Black Sea Rotational Force first stood up in 2010 and is tasked with similar regional security partnership missions with southern and central European countries.

“The Marines are very expeditionary,” said Nicholson, explaining why SPMAGTF-12 was especially suited for the Uganda mission. “This group brings a unique set of people and a unique set of skills.”

The task force teams will return to Sicily in late March before the second rotation, SPMAGTF 12.2, takes over and continues to send security and logistics cooperation teams into Uganda and other African nations taking up the fight against terrorism on the continent.

During a week of marksmanship shoots in late February, Marine coaches followed their Ugandan counterparts closely, scrutinizing everything from foot placement to eye relief. They teach shooting and surviving by the numbers: “acquire your target, focus on your front sight post, slow steady squeeze.”

“We used to think of ourselves as engineers, but now, after training with the Marines, we know we are soldiers first,” said UPDF 1st Lt. Martin Oorech.

The lynchpin of the task force’s doctrine of capacity building lies in the hope that the next time their students need to raise their rifles in combat, they won’t need the Marines.

At the end of each training session the Marine speaking calls out an “oorah” that is returned by dozens of UPDF troops in a uniform roar.

The Ugandan soldiers then clap a quick rhythm and chant “asante sana,” a Swahili thank you.

http://www.marines.mil/unit/marforres/Pages/SmallfootprinthighpayoffUSMarineteamtrainsUgandanforcestofacealShabaabLRA.aspx#.T2dk8Hl62Sq

3/14/2012 By Cpl. Jad Sleiman , Marine Forces Reserve

KAMPALA, Uganda — A thousand miles from the nearest major American base, about 30 U.S. Marines have been training a company of Ugandan soldiers for the fight against terrorism in East Africa since arriving in country, Feb. 3.

Special Purpose Marine Air Ground Task Force 12, the Marines’ Sicily-based parent command, is tasked with sending small training groups into Africa to partner with local militaries in an effort to indirectly blunt the spread of extremist groups across the continent.

The Uganda team of force reconnaissance, infantry, and combat engineering Marines first covered the use of a variety of weapons systems, marksmanship and field medicine, common soldiering skills Ugandan leaders say their men can use against the brutal Lord’s Resistance Army. More specialized follow on training began March 5 and is designed to help the Ugandan field engineers counter al-Shabaab insurgency tactics in Somalia, where urban obstacles and IEDs reminiscent of the war in Iraq are common.

“We are answering a stated need by our African partners,” said Lt. Col. David L. Morgan, commander of SPMAGTF-12 and 4th Force Reconnaissance Company. “Our mission in Uganda is yet another example of what this versatile force can do.”

The task force has dispatched teams across a wide swath of Africa over the course of their six month deployment in support of Marine Forces Africa, sending anywhere from five to 50 Marines into partner nations for days to months at a time. The unit is among the first of its kind and the mission in Uganda is one of its last.

From al-Shabaab to the LRA

“The soldiers on training will use the acquired knowledge in war-torn Somalia and in the hunt down of fugitive LRA commander Joseph Kony wherever he is,” said Ugandan People’s Defense Force Lt. Col. Richard C. Wakayinja, a senior officer in the field engineering unit training with the Marines.

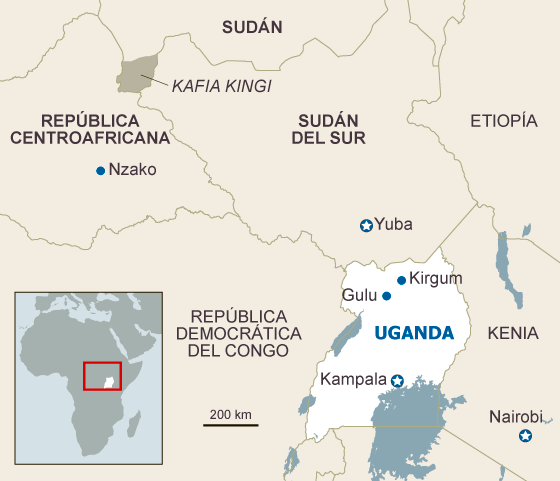

The UPDF is simultaneously providing the bulk of the more than 9,000 African Union peacekeepers engaging al-Shabab in Somalia while also staying on the hunt for Kony and his militia as they skirt the dense wilderness of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and South Sudan.

Their membership estimated to be in the hundreds, the cultist LRA is condemned by international human rights groups for a lengthy list of atrocities that includes mutilating living victims and forcing children into their ranks as either soldiers or sex slaves. The Obama administration ordered 100 combat advisers into central Africa last fall to aid in the hunt for their elusive Ugandan leader.

Al-Shabaab, which officially became a part of al-Qaida’s terrorist network in February, claims responsibility for the 2010 twin bombings in Kampala that killed 74 as they watched a World Cup final on television. The group also banned foreign aid agencies from Somalia as drought and famine ravaged the region last year.

Mogadishu-specific segments of training are scheduled to go over common combat engineering skills used to harden occupied urban spaces against complex attacks involving dangers like sniper and rocket fire as well as how to blast through enemy obstacles and difficult terrain. Another major focus will be on how to find IEDs before friendly forces get too close, said US Marine Maj. Charles Baker, the mission officer in charge.

“We’ve got force reconnaissance and engineers here together, that gives you the route reconnaissance skills,” he said, adding that the U.S. government would provide the UPDF with engineering equipment and vehicles worth about $8 million.

Shifting to a smaller footprint

U.S. military officials say mission’s like SPMAGTF-12’s could become more common place as troop levels in Afghanistan drop in line with an approaching 2014 combat mission end date. The 180-strong unit was formed over the summer of 2011 from Marine Forces Reserve units based across the country and equipped with two KC-130 Hercules aircraft to ferry teams to and from African countries.

“Because of the past ten years, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, there haven’t been a lot of forces available for Africa,” said Army Maj. Jason B. Nicholson, Chief of the Office of Security Cooperation at the U.S. Embassy in Kampala and former Tanzania foreign area officer.

SPMAGTF-12 has so far sent small teams into five African nations, including some threatened by a North African franchise of Al Qaeda attempting to spread its influence known as al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb or AQIM. The small task force team working with the UPDF represents one of the first significant security cooperation missions undertaken by the DoD in Uganda, a nation more accustomed to State Department interaction.

Undersecretary of the Navy Robert O. Work singled out the task force as a prime example of the type of “low footprint, high payoff operations” the White House is seeking as a means of maintaining global defense postures as the Pentagon pledges to cut at least $450 billion in defense spending over the next decade. The Corps is slated to reduce its active-duty troop strength from the current 202,000 to 182,100, leaving the force with about 7,000 more Marines than it carried before 9/11. In Uganda and Africa in general, US officials say, less can still be more.

A smaller U.S. force has the flexibility to move quickly, such as when a Djiboutian motor pool requested the task force’s help while preparing to deploy their first units to Mogadishu only weeks before their departure date last December. Using a small group like the one in Uganda, said Nicolson, can also simplify the complex politics associated with deploying and hosting troops in a foreign nation. Army Gen. Carter Ham noted African nations’ reluctance to host large numbers of U.S. troops as one reason for U.S. Africa Command’s headquarters to remain in Europe despite growing threats in Africa during testimony to Congress, Feb. 29.

The speed and maneuverability of slender teams, however, comes at a cost. As they partner with the UPDF, the Marines’ closest major source of U.S. support is Camp Lemonnier near Djibouti City, Djibouti. They and other task force teams operate, as unit leadership say, “alone and unafraid,” leveraging their needs against local resources and the limited supplies they can bring with them.

“We’ve grown used to operating near a base that can supply us with what we need,” said Gunnery Sgt. Brian Rivero, staff non-commissioned officer in charge of the mission. “Down here we’ve had to rely on the Ugandan economy for everything from food and water to medical care.”

The task force is built around 4th Force Reconnaissance Company, based in Alameda, Calif. The special operations capable unit is suited for what’s called “deep recon,” whereby teams operate well behind enemy lines with little to no support. Their Uganda partnership is strictly a train and equip mission designed to allow the UPDF, widely considered one of the most professional militaries in the region, to stay on the lead. The Marines in Uganda are working on friendly turf far from hostile fire, but remain very much on their own.

“The complexity of this endeavor cannot be understated,” said Morgan. “Despite the logistical challenges associated with acquiring the necessary ammunition and equipment for Ugandan forces, and complexities associated with operating in Africa, the men and women of the SPMAGTF have endured and created a superior program and partnership.”

Future expeditions

Marine leadership have grown to fear the specter of the Corps becoming a “second land Army” with dwindling relevance after more than a decade of static fighting in the Middle East. SPMAGTF-12’s missions on the continent could represent an early example of a long heralded Marine Corps return to globetrotting, quick reaction operations.

Already, a separate Marine Air Ground Task Force is planned for the Asia-Pacific region with troops basing in Darwin, Australia. The Black Sea Rotational Force first stood up in 2010 and is tasked with similar regional security partnership missions with southern and central European countries.

“The Marines are very expeditionary,” said Nicholson, explaining why SPMAGTF-12 was especially suited for the Uganda mission. “This group brings a unique set of people and a unique set of skills.”

The task force teams will return to Sicily in late March before the second rotation, SPMAGTF 12.2, takes over and continues to send security and logistics cooperation teams into Uganda and other African nations taking up the fight against terrorism on the continent.

During a week of marksmanship shoots in late February, Marine coaches followed their Ugandan counterparts closely, scrutinizing everything from foot placement to eye relief. They teach shooting and surviving by the numbers: “acquire your target, focus on your front sight post, slow steady squeeze.”

“We used to think of ourselves as engineers, but now, after training with the Marines, we know we are soldiers first,” said UPDF 1st Lt. Martin Oorech.

The lynchpin of the task force’s doctrine of capacity building lies in the hope that the next time their students need to raise their rifles in combat, they won’t need the Marines.

At the end of each training session the Marine speaking calls out an “oorah” that is returned by dozens of UPDF troops in a uniform roar.

The Ugandan soldiers then clap a quick rhythm and chant “asante sana,” a Swahili thank you.

http://www.marines.mil/unit/marforres/Pages/SmallfootprinthighpayoffUSMarineteamtrainsUgandanforcestofacealShabaabLRA.aspx#.T2dk8Hl62Sq

Ejército ugandés presume muerte de guardaespaldas de Joseph Kony

Ejército ugandés presume muerte de guardaespaldas de Joseph Kony

http://www.24-horas.mx/ejercito-ugandes-presume-muerte-de-guardaespaldas-de-joseph-kony/Ejército ugandés presume muerte de guardaespaldas de Joseph Kony

Fue identificado como Binani, emboscado cuando regresaba a su base en Garamba, después de entregar mercancías y provisiones a su jefe, ugandés líder del LRA y acusado por la Corte Penal Internacional de delitos como violación y mutilación contra unos 30 mil niños.

EFE

enero 21, 2013 1:12 pm

KAMPALA. El Ejército de Uganda aseguró hoy haber acabado, en la República Centroafricana, con el jefe de los guardaespaldas de Joseph Kony, líder de la guerrilla rebelde de origen ugandés del Ejército de Resistencia del Señor (LRA, por sus siglas en inglés).

El portavoz de las Fuerzas Armadas ugandesas, Felix Kulayigye, señaló hoy que el rebelde abatido fue identificado sólo como Binani, mientras que otro rebelde corrió la misma suerte y un tercero resultó herido.

“Binani era un hombre clave en las filas de Kony. Nuestras fuerzas le mataron junto a otro rebelde, hirieron a un tercero y se incautaron de dos ametralladoras”, afirmó Kulayigye.

Otras fuentes de inteligencia que solicitaron el anonimato apuntan a que Kony habría enviado recientemente a Binani al norteño parque natural de Garamba, en la República Democrática del Congo (RDC).

Según esas fuentes, los militares ugandeses le habrían dado caza mientras regresaba a su base en Garamba, después de entregar mercancías, como marfil, y provisiones a Kony, supuestamente establecido en la República Centroafricana.

Hace meses, varias informaciones apuntaban a que el LRA podría estar obteniendo financiación a través de actividades como el tráfico de marfil.

Desde que comenzó su lucha, a finales de los años ochenta, Kony y sus secuaces han secuestrado, torturado, violado, cercenado y matado a decenas de miles de personas.

“La lucha comenzó para defender a la población acholi de las represalias del presidente (de Uganda), Yoweri Museveni”, dijo a Efe Kenneth Banya, antiguo consejero de Kony y ex número tres del LRA en los 18 años que estuvo en las filas de los rebeldes, para los que aseguró haber sido reclutado por la fuerza.

Kony nació en Uganda en 1961 pero su influencia abarca parte del Congo y la República Centroafricana, donde se encontraría actualmente.

A la caza de Kony, el lider del Ejército de Resistencia del Señor.

A la caza de Kony, el lider del Ejército de Resistencia del Señor.

http://internacional.elpais.com/internacional/2014/03/07/actualidad/1394223432_071887.html

Los conflictos de Sudán del Sur y República Centroafricana debilitan el cerco al ugandés

ÓSCAR GUTIÉRREZ (ENVIADO ESPECIAL) Kampala 7 MAR 2014 - 22:46 CET

Kafia Kingi es un buen pedazo de tierra muy frondosa localizado en el triángulo que une Sudán, República Centroafricana y Sudán del Sur. En disputa entre los dos vecinos sudaneses, es el norte el amo y custodio del territorio. Allí es hacia donde señalan los últimos guerrilleros desertores del cruento Ejército de Resistencia del Señor (LRA, en sus siglas en inglés). Allí, según los trabajos realizados por una de las organizaciones que sigue la pista al LRA, The Enough Project —con acceso a fuentes militares y excombatientes—, se encuentra parapetado su general al cargo, uno de los señores de la guerra africanos más buscados por sus atrocidades: Joseph Kony, el místico líder rebelde de los 10 mandamientos, perseguido por la Corte Penal Internacional.

¿Por qué no se le da caza? “Es un área muy vasta, como una jungla”, explica el analista de The Enough Project Kasper Agger, desplazado a Kampala, capital de Uganda, para dirigir el rastreo del LRA. “Hay imágenes tomadas por satélite, pero es difícil distinguir entre un cazador, un bandido o un rebelde del LRA…”. Y lo que tiene peor solución y ha hecho saltar las alarmas de los que persiguen al LRA, las guerras abiertas en los vecinos Sudán del Sur y República Centroafricana han distraído fuerzas y atención del cerco a Kony, que rondará hoy los 53 años. Un dato para el detalle: el medio millar de soldados sursudaneses que apoyaba la exigua misión contra el LRA bajo sello de la Unión Africana ha desviado su paso a combatir el levantamiento interno contra el presidente de su país, Salva Kiir.

Ni las filas del LRA están ya muy nutridas, los cálculos más generosos hablan de 700 miembros —incluyendo a no combatientes—, ni existe el apoyo social con el que nació a finales de los ochenta en el norte de Uganda. “Ni siquiera es una amenaza para Uganda”, afirma Agger. “Kony quiere sobrevivir, pero no regresar”. El LRA no es esa guerrilla formada en la región de mayoría étnica Acholi contra la que se cebó el actual presidente ugandés, Yoweri Museveni, al mando del entonces Ejército de Resistencia Nacional, hoy las Fuerzas Armadas regulares. Lo que no se borra de la mente son las atrocidades cometidas por un líder rebelde aupado entre el misticismo de su figura y el seguimiento a sangre de los 10 mandamientos; alabado por una guerrilla que ha reclutado a miles de niños, muchos tras ser obligados a matar a su familia, que ha usado a niñas como esclavas sexuales, que ha drogado para el combate a menores, y ha arrasado poblaciones a su paso, 320.000 civiles permanecen aún desplazados. ¿Y si se da caza a Kony? “Esa es la pregunta del millón”, contesta Agger, “pero seguro que muchos desertarían”.

Eso si se enteran porque el LRA está dividido geográficamente y sus milicianos campan entre Sudán, Congo y República Centroafricana. “El reto”, señala Paul Ronan, analista de The Resolve, “está en la República Centroafricana”. Según la información reunida por esta organización, que como The Enough Project y la popular Invisible Children —autora de la campaña Kony2012— sigue el rastro del LRA, hombres a las órdenes de Kony se entremezclan en el sureste de este país con guerrilleros del Seleka, grupo centroafricano de origen musulmán que apoyó el golpe de Estado de Michel Djotodia en marzo de 2013. “Es difícil saber si las atrocidades en esas comunidades las hacen unos u otros”, admite Ronan.

Precisamente Djotodia —ahora exiliado— se hizo eco el pasado noviembre de un deseo de apertura de diálogo llegado en carta con puño y letra del mismísimo Kony. Según documentó Ronan, el presidente interino centroafricano mandó una misión militar con medicinas y comida a la localidad de Nzako, donde aguardaba un grupo de rebeldes del LRA. Las provisiones se las quedaron, pero se dieron a la fuga y fueron emboscados por tropas ugandesas. Había sido una treta.

Y si fuera poco, Ronan señala otra grieta en el combate al LRA: el apoyo de militares ugandeses al presidente sursudanés Salva Kiir: unos viejos lazos que ayudan a explicar la laxitud de Sudán con Kony y los suyos. “Prácticamente todos los soldados que luchan contra el LRA son ugandeses”, explica el analista, “y Uganda está derivando recursos hacia Sudán del Sur”. Y ahí se quedarán hasta que pase lo peor, según ha anunciado el Gobierno de Kampala.

De lo que no cabe duda es de que, como señala Invisible Children, las víctimas a manos del LRA han caído drásticamente en los últimos tres años. Según los datos de esta organización, en el último mes solo se ha podido documentar la muerte de un civil a manos del LRA. El pasado año fueron 75, mientras el cómputo desde diciembre de 2008 asciende a 2.329 víctimas mortales. Todo esto coincide con la llegada en 2011 de un centenar de asesores estadounidenses en apoyo de los soldados ugandeses.

Pero el combate a Kony no se libra solo con satélites y misiones a países vecinos. En el norte de Uganda, en localidades como Gulu o Kitgum, se sigue luchando por la rehabilitación de excombatientes, mujeres de exmiembros del LRA y niños nacidos en cautiverio; víctimas de la violencia sexual, de heridas de guerra, de malos tratos.... “Las comunidades no están preparadas para recibir a los niños soldado”, afirma James Ronald Ojok, investigador de Refugee Law Program. “Allí, las aldeas rechazan acoger y expulsan a las mujeres de combatientes en activo o en paradero desconocido”.

Muchos ex niños soldado, según ha registrado esta organización con sede en Kampala, no son aceptados por sus padres o incluso llegan a sentirse rechazados por la escuela y vuelven a coger las armas, ahora en poder del Ejército. “¿Qué van a hacer si llevan toda su vida siendo guerrilleros?”. Es el estigma que dejó Kony en sus vidas. ¿Llegan muchos desertores? “Desde que se fueron a República Centroafricana y Congo, menos; hay mucha distancia y miedo”, responde Ojok, “pero si se acaba el conflicto, recibiremos a muchos”.

ivan_077- Staff

-

Cantidad de envíos : 7771

Cantidad de envíos : 7771

Fecha de inscripción : 14/11/2010

Why is the US hunting for Joseph Kony?

Why is the US hunting for Joseph Kony?

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2014/05/why-us-hunting-joseph-kony-20145716731355345.html

Why is the US hunting for Joseph Kony?

With major ongoing conflicts in countries surrounding Uganda, it is surprising that the US continues the hunt for Kony.

Catching Joseph Kony would be an easy political win for the Obama administration[AP]

In February US President Barack Obama publicly condemned a bill criminalising homosexuality in Uganda, cautioning Uganda's President Yoweri Museveni that "enacting this legislation will complicate our valued relationship". Yet five weeks later Obama notified Congress that the US was sending 150 Air Force Special Operations forces and other personnel, plus several CV-22 Ospreys and refuelling aircraft, to aid Uganda's 25-year pursuit of Joseph Kony, leader of the notorious Lord's Resistance Army (LRA). Shortly after, the US military abruptly announced that it was pulling the aircraft out of the mission.

What is going on? These twists and turns are puzzling - and troubling - and not just because they undercut well-deserved US denunciation of Uganda's new anti-homosexuality law.

Moreover, the recent dispatch of US military support to Uganda to hunt Kony comes at a time when the threat posed by the LRA is vastly overshadowed by far more troubling armed violence in the three Central African countries where LRA fighters are located.

In the Central African Republic (CAR), opposing armed groups have for months committed massive atrocities and pushed an already weak and troubled state to the brink of collapse. Immediately east of CAR, the world's newest nation - South Sudan - is embroiled in an armed conflict that began in December as a power struggle within the country's ruling political party, but has escalated into widespread fighting that threatens an extended civil war, with dangerous ethnic overtones. And just to CAR's south, in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the long-suffering population continues to be preyed upon by many armed groups besides the LRA, not least the country's army.

While the US has voiced alarm about these emergencies, until recently it has provided limited practical assistance. US Secretary of State John Kerry's recent visits to South Sudan and DRC could change this, although it is as yet unclear what the effect of these visits will be. In this context, the high priority of the LRA in US policy is surprising.

The dissolution of the LRA

Originally an insurgency based in northern Uganda, the LRA became notorious between 1988-2006 for atrocities against civilians (including killings, mutilations and abductions), although Ugandan government army abuses and structural violence was even more deadly, especially the government policy of forced internal displacement of 1.2 million people at the epicentre of the war.

Listening Post - Feature: Kony 2012: The new kids on the media block

Following failed peace talks in late 2008, the LRA scattered across wide swaths of heavily forested and lightly administered territory in adjacent parts of the DRC, South Sudan and CAR. There, an initial phase of large-scale LRA killings, abductions and civilian displacements in the region has been succeeded by dwindling rebel strength. Operating far from their original northern Uganda base - and hunted, if sporadically, by Ugandan and other national armies since (recently operating under an African Union mandate) - the LRA managed their last large-scale attacks in the totalling in early 2010.

Since then they have splintered into ever smaller, increasingly uncoordinated bands totaling probably less than 200 fighters. When the last sizable group of 19 LRA fighters abandoned the movement and came out of the bush in December 2013, for example, our interviews with this group showed how they had no contact with the rebel high command for for up to two-and-a-half years.

While some LRA attacks and (mostly short-term) abductions continue, the frequency and severity of such incidents has fallen to a level where the rebel group has become a relatively minor threat.

Indeed, violent killings attributed to the LRA in rebel-affected areas of northeastern DRC last year occurred at a rate far less than in the US: 2.9 per 100,000 population (our estimate) vs 4.8 per 100,000 in the US. And although no similar statistics are available for the CAR or South Sudan, the armed conflicts currently under way in both these countries have undoubtedly resulted in casualties and displacements far surpassing - and unrelated to - those caused by the LRA .

Why is Kony still important?

Yet the US has just committed more military personnel and equipment to hunt Kony. In October 2011 when the first 100 US troops were deployed, the LRA was already much weakened. This was even more the case by early 2014 when the latest US military commitment was announced.

So, again, what is going on? The only reasonable explanation is that the LRA has become an almost exclusively internal US issue, driven by domestic US politics rather than realities on the ground in Central Africa.

Inside Story - 'Kony 2012': The future of activism

First, there is the influence of the advocacy groups. The most visible of these is Invisible Children (IC). Launched by a short film of the same name in 2004, IC became a US popular culture phenomenon, lucrative fund raiser, and powerful voice focusing on the LRA. Indeed, IC - along with the Enough Project and Resolve - was crucial in convincing the Obama administration to send the first advisers and supporting equipment to help Uganda "capture or kill" Kony.

Second, for the administration (with rare bipartisan support in Congress), the LRA issue seemed an easy political win: With relatively little effort - a handful of troops - the US could help catch one of the world's most wanted men while satisfying an important domestic political constituency. One former US government source told us that Obama never directly informed Museveni about this initial dispatch of US troops, announcing it instead in a Washington press conference - an unmistakable signal of the policy's centre of gravity, and to which audience the policy needed most to be communicated.

Third, shifting US power relations with respect to the LRA policy proved highly influential. The centre of gravity over the last year has swung towards the Department of Defense, with a more pro-active AFRICOM command promoting greater engagement in the hunt for Kony. This could explain the delivery of the Osprey aircraft. The fact that they were abruptly recalled only a month later reinforces our argument that US decisions, even by the US military, are being taken independently of the situation on the ground.

By framing the LRA issue as a personal and technical military problem, rather than a political one, a single goal - with a short timeline - has been set: to catch Kony. In this scenario, both Invisible Children and the Obama administration are caught in a trap of their own making (even if the trap was bated by the Ugandan government, which has long promoted the same view of the LRA "problem").

In this situation, US withdrawal from the hunt would be perceived as a failure, both for the government and advocacy groups such as Invisible Children. Pressure to succeed is heightened by the fact that momentum surrounding the LRA issue is diminishing, or has already passed. Support for IC has recently plummeted: donations are sharply down resulting in a one-third reduction in staff and many programmes cut or eliminated. In recent interviews, remaining IC staffers indicate they would not mind moving on, but feel stuck in trying to raise attention for a dying cause. A similar logic holds for the Obama administration: If it is to gain further political capital out of the LRA issue it needs to act - and succeed - fast.

In sum, the projection of US internal politics and the influence of US advocacy groups into the violent Central African region has led to an extremely cynical situation: An important US intervention in what constitutes a minor problem is occurring in the midst of truly large-scale violence and instability which has failed to prompt commensurate US political or material support.

This myopic and distorted vision has exaggerated the significance of the LRA and obscured the major drivers of insecurity and armed violence in Central Africa, to the detriment not only of those caught up in that violence but genuine strategic and humanitarian interests.

Kristof Titeca is based at the Institute of Development Policy and Management (University of Antwerp) and the Conflict Research Group (Ghent University). He is currently a visiting fellow in the Department of International Development, London School of Economics.

Ronald R Atkinson is a Senior Research Associate at Walker Institute of International and Area Studies, University of South Carolina.

The views expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera's editorial policy.

Source:

Al Jazeera

ivan_077- Staff

-

Cantidad de envíos : 7771

Cantidad de envíos : 7771

Fecha de inscripción : 14/11/2010

Temas similares

Temas similares» Golpe Militar en Egipto

» Renuncia el jefe del Ejército colombiano.

» Soldado del ejército, jefe de banda de robacarros, en MartínezdelaTorre

» [Resuelto]El Asunto Siria

» Acusan a ex presidente y Jefe del Ejército de Pakistán de traición.

» Renuncia el jefe del Ejército colombiano.

» Soldado del ejército, jefe de banda de robacarros, en MartínezdelaTorre

» [Resuelto]El Asunto Siria

» Acusan a ex presidente y Jefe del Ejército de Pakistán de traición.

Página 1 de 1.

Permisos de este foro:

No puedes responder a temas en este foro.

Índice

Índice Últimas imágenes

Últimas imágenes Registrarse

Registrarse Conectarse

Conectarse