Poor 'hood, Mean 'hood: the Violent History of Rivera Hernandez, Honduras

Página 1 de 1.

Poor 'hood, Mean 'hood: the Violent History of Rivera Hernandez, Honduras

Poor 'hood, Mean 'hood: the Violent History of Rivera Hernandez, Honduras

El barrio más peligroso de la ciudad más peligrosa.

Fuente: http://www.insightcrime.org/investigations/gang-history-rivera-hernandez-honduras

Reporte completo en español en PDF: http://www.insightcrime.org/images/PDFs/2015/MarasHonduras.pdf

Poor 'hood, Mean 'hood: the Violent History of Rivera Hernandez, Honduras

Written by Juan Jose Martinez d´Aubuisson with illustrations by German Andino Woods Wednesday, 09 December 2015

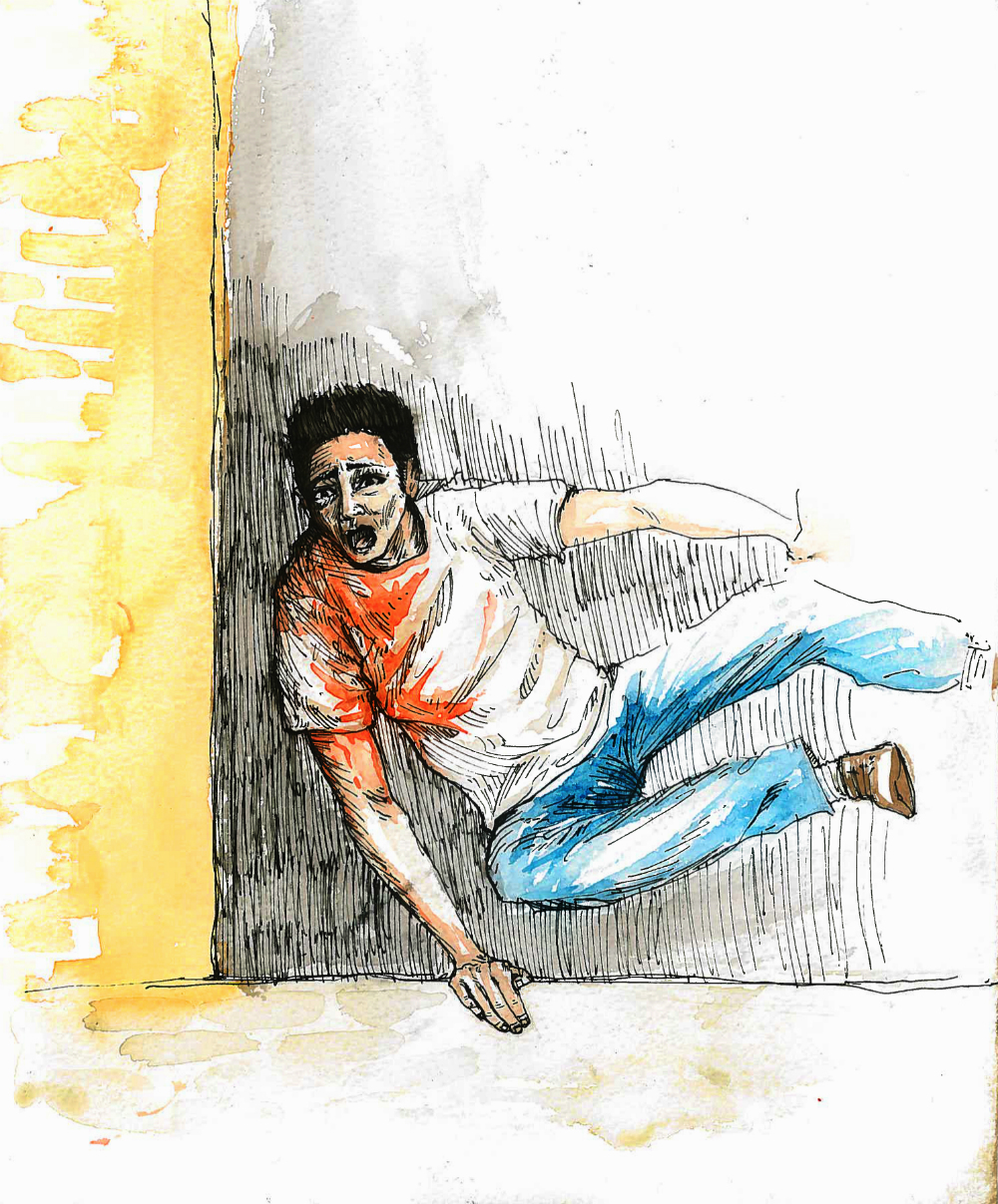

Calaca, an MS13 gang member in San Pedro Sula

In the neighborhood of Rivera Hernandez in San Pedro Sula, the State's absence is felt everywhere. Six gangs fight for control of one of the poorest sectors of Honduras' industrial capital. This is the story of that neighborhood. This is the story of the people who live here, who fall like dominos, one after another, in an endless battle.

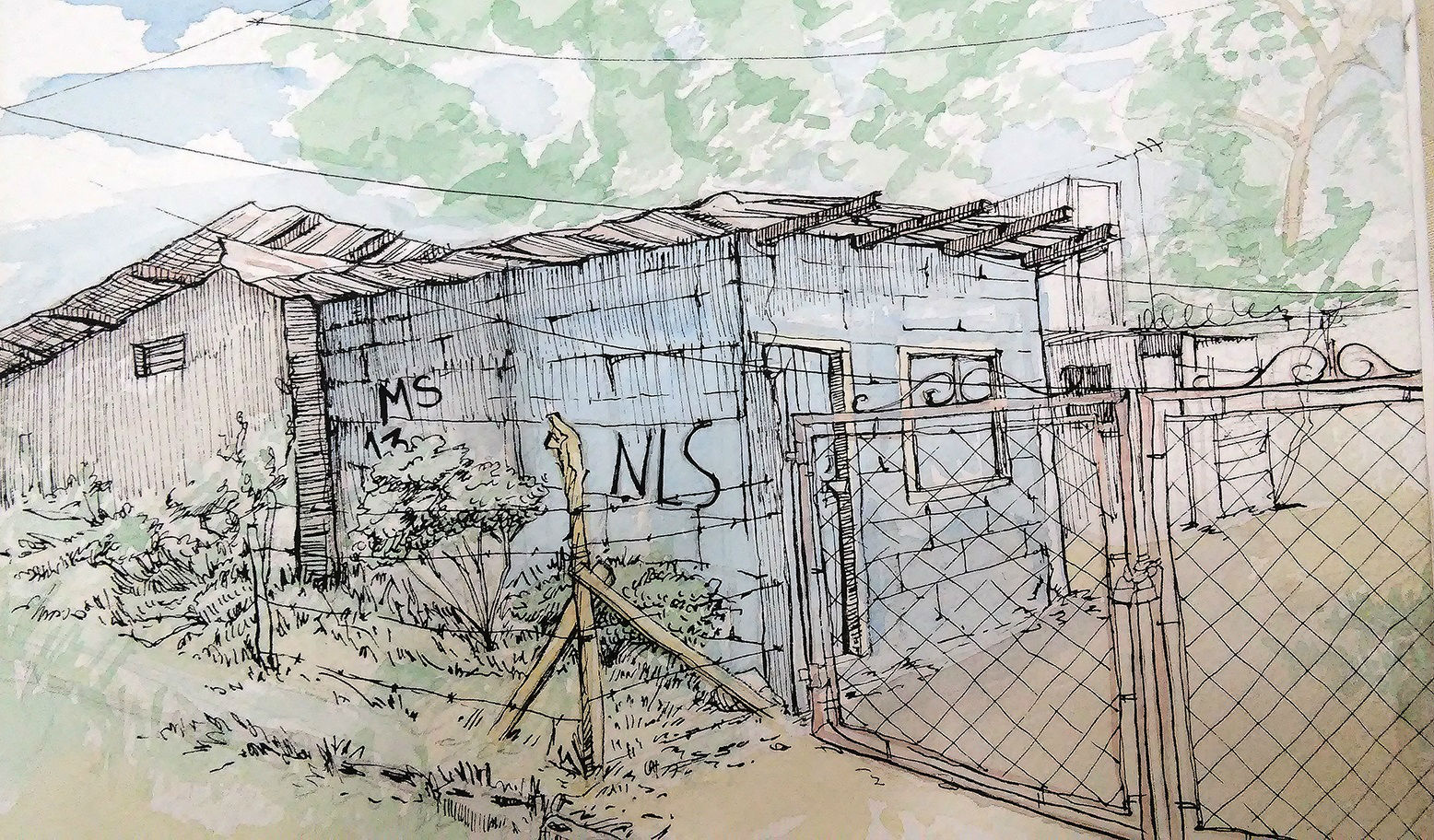

The house. Rivera Hernandez neighborhood, San Pedro Sula. 2010.

Melvin Clavel finally returned, several years after he left home. Like many young men in San Pedro Sula, he left to try his luck at the nearest sea port, Puerto Cortes. That is where he became a sailor and spent several years getting on and off fishing boats. Melvin Clavel collected all that he could from the Honduran ocean and saved up money. After a while, he left the swaying of the ocean and planted himself back upon solid ground, back where he grew up in Sinai, a district located in the enormous neighborhood known as Rivera Hernandez, the most dangerous neighborhood in San Pedro Sula.

But the ocean had rewarded Melvin nicely. After several years of hard work on board these floating factories, he managed to save enough money to build a big house and start a family. He became perhaps the richest man in Sinai, a district located deep within the vast wretchedness of Rivera Hernandez. His sacrifice at high sea even allowed him to start a grocery store, based out of a room in his house. The Clavels' grocery store was formidable. Melvin personally attended to the store and oversaw the construction of a large cement shelf in front of his house. He also had steel bars and a window installed in order to better attend his clients. Then came the boxes of butter, candies, gas cylinders, cases of Coca Cola and everything else that was needed to build up the best business in the neighborhood.

This article is the first in a series looking at gang operations in Honduras. It is the result of a collaboration between InSight Crime, El Faro, and Revistazo. Read a version of this article in Spanish here. See the full version of InSight Crime's report on Honduras gangs here (pdf). Read the report in Spanish here (pdf).

But Melvin Clavel knew where he lived and that he was in the middle of an ecosystem of violence, so prevalent in Sinai and Rivera Hernandez. To protect himself, he bought a 12-gauge shotgun and a pistol. He wasn't about to let others take away all that he had earned while working at sea.

At the time, Sinai was dominated by a group of thugs known as "The Ponce." They weren't a very original group.

The thugs did what all gangs do in these areas: claim territory, battle neighboring gangs to the death, and extort people, a practice that is aptly known as collecting a "war tax." Melvin had grown up with the leader of the Ponces, a young man called Cristian Ponce who was known throughout the neighborhood for his use of violence. They were neighbors for many years; their mothers knew each other, and Cristian and Melvin were close basically their whole lives.

The gang killed Melvin at the end of 2012, while he was unarmed and had his back turned. They shot him in the head three times as he was taking down some boxes of butter.

Nonetheless, Melvin's rapid prosperity earned attention from Cristian and other members of the Ponces. After two years, the story began to play out as it usually does: a boy visited Melvin's store and told him that he must pay the war tax like all the other businesses in Sinai. If Melvin refused, the gang would have to kill him. Outraged, Melvin refused, brandished his shotgun and chased the boy out of the store, with a message for Cristian Ponce: if he wanted the money, he would have to come get it himself. Calling the police was never an option for Melvin. He trusted his weapons more than the police.

The gang killed Melvin at the end of 2012, while he was unarmed and had his back turned. They shot him in the head three times as he was taking down some boxes of butter. He suffered for a moment in front of his children and later died in San Pedro Sula's public hospital. The killer chosen by Cristian was Cleaford, a youth that Melvin didn't associate with the group and who therefore could approach him without drawing suspicion.

That same night, while the Clavels cried over the dead fisherman, Cristian Ponce and his gang entered Melvin's store and took the candies, the gas cylinders, the boxes of Coca Cola, as though they were collecting the spoils of war...

People in Sinai say that the Ponces worked throughout the night. After they were done with the merchandise, they started moving the furniture out of the house, the clothes, the television. The house was completely emptied. But the Ponces wanted more and, like a whirlwind, they tore off the roof, tiles, door frames, toilets, lamps. They sucked out everything that Melvin Clavel had earned at sea. His wife and two daughters never returned. They were terrified of Cristian and his band of killers and thieves, so they sought refuge and fled the area, the furthest away they could get from Sinai and Rivera Hernandez. As months passed, Cristian took over the house, which became the headquarters for the Ponces. From there they were able to wage war with neighboring gangs: the Vatos Locos, the Barrio Pobre 16, the Tercereños, the Mara Salvatrucha 13, and the feared Barrio 18, the most violent gang in Rivera Hernandez. This was how the house of Melvin Clavel became a den for thieves.

The history of death in Rivera Hernandez

The day Jose Caballero was killed, he was in a meeting discussing the need for a communal cemetery. It was the 1970s, and what is now a dense web of dark alleyways, dirt roads, and run-down houses was at that time enormous and lush cane fields and pastures. Jose Caballero and another group of men had taken over these lands, as was often done back in those days, by grouping together a large number of homeless people, of which there were many after Hurricane Fifi. They took over empty lots in the dead of the night and hoped that the property didn't belong to anyone important. If all went well and the land belonged to the state, Jose Caballero and the others could negotiate and organize the sale of the plots, keeping a slice of the profits for themselves.

The day he was killed, Jose Caballero made a proposal: that the cemetery be named after the first dead person who was buried there. Everyone agreed. After the meeting, a man approached Jose and asked for his money back, since that man had bought a plot of land where another family was already living. Jose refused, and the cemetery now bears his name. The man took a shoemaker's knife to Jose's throat, and Jose bled to death in front everyone.

Almost all of the founders of Rivera Hernandez are dead. And several of the old men who tell these stories were their killers.

Almost all of the founders of Rivera Hernandez are dead. And several of the old men who tell these stories were their killers. Mr. Salomon, the man who replaced Jose Caballero as head of the neighborhood board, was killed with a machete by Mr. Andres, a battered old man who now complains about the five bullets he once received from Salomon, more than 30 years ago, before dying from wounds he suffered from a blunt machete.

At some point before these deaths, Carlos Rivera, the president of the first neighborhood board in this area, was killed on the steps of San Pedro Sula's Attorney General's Office. In his honor, they named the area and a school after him. The name of the neighborhood was also taken from Hernandez, one of the first owners of these lands.

The conflicts in Rivera Hernandez seem to follow a pattern. They are small wars fought over resources or land. Not large estates, but small plots, the majority of which are a few square meters that could barely fit a tent.

Juan Ramon is among those who talked to us about those violent years when the neighborhood was founded. We found him by asking a question all anthropologists want to ask before dying: "Can you take me to the oldest man in the neighborhood?" Juan Ramon is small and dark-skinned, an evangelical pastor for the last 30 years. He isn't technically the oldest man in Rivera Hernandez, but he is one of the most respected members of the community. He likes to talk, tell stories about all those deaths he witnessed when Rivera Hernandez was established. He knows about all of the deaths. At one point, he told a story about a murder, then mentioned that if the killer wasn't already dead, then he surely lived just a few blocks from Juan Ramon's house, and probably spoke with Juan Ramon just "a little while ago."

The kids who are now fighting over this same territory are the grandchildren of those who were involved in the bloody founding of Rivera Hernandez. Just like their ancestors, the gang members water this poor neighborhood with their blood on a daily basis, in order to maintain territorial control.

The old men say that a few months after having established the first settlement, another group of people arrived in Rivera Hernandez, and then another. The settlements kept drawing more and more people, as if with a magnetic force. Some settlements employed desperate survival strategies, like when the founders of the "Celio Gonzalez" neighborhood decided to name their settlement in honor of the current president, hoping to please him and that he would take pity and would not force them off the state-owned land.

Another man baptized his neighborhood "Human Settlements." The community thought that this name evoked human rights, and that perhaps by reminding the government that they were people, this would prevent authorities from driving them off the property. Eventually, the residents were able to keep their territory, and the neighborhood became an enormous sprawl known for its wars between rival gangs and criminal groups.

Rivera Hernandez has always been known for its violence. It's an area with many people living in tight quarters, in poor conditions with few resources, where what little there was, was fought over with machetes. The elderly remember a long list of dead and injured as a result of small disputes. The cemetery is full of young men and women who were murdered by their neighbors. Nonetheless, it was a primarily one-on-one style of violence, with little structure or involvement of large groups. Most fighting occurred between families over the death of one of their relatives.

The first gang to arrive in this area was the Barrio Pobre 16, which was established at the end of the 1980s, according to the community elders. Veterans of the gang say members included deportees from the United States. The Barrio Pobre 16 was a Latin gang formed by Mexicans that originated in southern California. Originally the gang's name was Barrio Pobre 13, but in San Pedro Sula, they want to differentiate themselves from the Mara Salvatrucha, or MS13, and of course, from the 18th Street, or Barrio 18, so they chose a number in the middle.

The Barrio Pobre 16 was a revelation for the youths of Rivera Hernandez. Those who had been deported from the US had tattoos, spoke English, wore flashy clothes, and were seen as the definitive, real-life image of modernity.

In just a few years, a young man from Rivera Hernandez transformed the Barrio Pobre 16 into a group of feared killers and extortionists who dominated the neighborhood. This young man was called El Yankee -- dark-skinned, strong, violent, all that is left of him is graffiti on a wall. Next to his initials, the graffiti artist drew a tomb and the phrase "in memory," followed by the initials of El Yankee's gang, BP XVI.

Gang histories are almost never written down -- gang members carry the memories to the grave, or they write it out on their skin in ink. Other stories are captured on the walls of slums and shantytowns. Like a Mayan monument, this particular concrete wall tells an interesting story. Above the memorial for El Yankee, someone, several years later, crossed out "BP XVI" with black paint and instead painted a formidable "MS X3." The small Barrio Pobre gang could not survive an assault by the two largest gangs in the Americas: the MS13 and the Barrio 18. A veteran of the Barrio Pobre XVI said that El Yankee died in a rain of bullets before his family. Another death that the Jose Caballero cemetery swallowed greedily.

Juan Ramon, the respected elder, finished his stories. I asked him if at some point he had ever killed or injured someone. He looked me intently in the eyes and told me that he had only shot at Salvadorans. He is not joking -- he was one of the recruits for the war between El Salvador and Honduras in July 1969, an ephemeral war that barely lasted 100 hours.

Although Juan Ramon is a man with a certain amount of power within the neighborhood, he does not live any differently than the others. His house is a flimsy structure like all of the houses in this area, whose roof is bombarded every two minutes by Jurassic-sized mangoes that make a tremendous din when they fall. His wife makes tortillas and baked beans cooked on a wood stove that fills each corner with smoke, as it does with all the houses in the neighborhood.

While the illustrator who accompanied me, German Andino, drew a portrait, Juan Ramon sat in his chair made of old woven rope -- surrounded by the halo of this mysterious wood smoke and accompanied by a group of his wife's screeching hens -- and looked at us with a face that was both happy and surprised.

Rivera Hernandez neighborhood. San Pedro Sula, beginning of 2013.

Melvin Clavel's house was nothing more than rubble. Of all the objects that had once filled the house just a few months earlier, nothing was left except for the roof, the floor and the cement-colored walls. The Ponces ate quickly. Where there were once shelves with treats, now there was now only trash and the blood stains where Melvin had been shot.

Something similar would happen to the Ponces' leader -- Cristian Ponce would eventually be assassinated by the Olanchanos, one of the most violent gangs in Rivera Hernandez. The Olanchanos are a strange mix of drug traffickers and thugs that the others gangs looked upon with respect. In some ways, the death was caused by

Cristian's younger brother -- he allowed the Olanchano hitmen to enter Cristian's house and gun Cristian down.

Afterwards, Cristian's little brother fled to the United States as an undocumented immigrant, and nothing else has been heard from him since. The Ponces that stayed behind behaved like a group of lawless thugs, betraying and killing each other. After Cristian's death, no one trusted anyone else, and everyone was watching their own back.

At the beginning of 2013, other gangs began coveting the neighborhood that the Ponces had dominated for years.

At the beginning of 2013, other gangs began coveting the neighborhood that the Ponces had dominated for years.

One section was stalked by the MS13, perhaps the largest gang in Rivera Hernandez. On the other side were their life-long enemies, the Olanchanos. Two streets down, the Vatos Locos cast a greedy eye. Two other small but ferocious gangs were also fighting to take over Sinai: the Parqueros and the Tercereños. These gangs made their own attempts to finish off what remained of Cristian Ponce's group. On top of all this, just one kilometer away, lurked the most feared and violent gang in the entire neighborhood: the Barrio 18.

As a result of these circumstances, several Ponce members deserted and joined the MS13. After this loss, Sinai was controlled by no more than five Ponce members. The other gangs had them cornered, but the Ponces would survive another year in the middle of the crossfire. By January 2014, the Ponces had increased their "war tax," charging their neighbors exorbitant amounts. They followed the same logic that Cristian had taught them: anyone who didn't pay, paid with their life.

One of these extortion operations targeted the Argeñal family, who owned a small store. The Argeñals were unable to pay the "tax" and tried to negotiate. But there was no room for leniency, and a few days later the Ponces kidnapped Andrea Abigal, the family's 13-year-old daughter. The police made a timid attempt to search for her and carried out a few raids. Afterwards, the girl's mother was left on her own, knocking on doors, begging for Andrea. The Ponces held Andrea captive for several days and after raping her, they cut her into pieces and buried her in the patio of Melvin Clavel's house. They say that while she was being mutilated, one of the Ponces called Andrea's mother on the phone, so that she would hear the shouts and the sounds of the machete. The mother talks very little now. She is not the same person she was before.

By doing this, the gang signed its own death warrant. The Olanchanos, upset with all the attention from the media and police, captured two of the Ponces and, after torturing them, killed them both. One appeared in a sack on the side of the road and the other was found by a local farmer several meters below ground. That left only two members of the Ponces. The entire family of one Ponce member was killed by the MS13, and the gang took all that was inside of the house as their bounty -- the same that had happened to the Clavel family. The other Ponce gang member still lives in the neighborhood. He told us his story and even allowed German to draw his portrait, but he does not leave his room. The day that he does, the MS13 will be there to make him pay for his mistake.

While we were conducting field research for this report, between February and June 2015, the houses of all the Ponce members were like vestiges of an ancient war. Vegetation was growing inside them. The ceilings and the doors had been removed months ago. Inside, all that remained were the walls, painted with the graffiti of dead gang members. One of the houses had a room flooded with greenish water swarming with mosquitoes. It was like a big factory for chikungunya, the malaria-like illness plaguing Rivera Hernandez.

No one wants to inhabit these ruins. Although these are large tracts of land, the community prefers to ignore them. They are left as nothing more than headstones of past deaths, dilapidated reminders of people who are no longer here. Only one of the Ponce ruins remains inhabited: by an elderly woman and an enormous dog, the group's mascot. The dog was supposed to watch over the property and the elderly woman -- it completed the first task, but not the second. One dark night, the woman left the house and walked across the patio, where the dog mauled her to death. Now the mutt lives alone, watching over the ruins of the property.

The Ponce gang's pet dog in Rivera Hernandez. Illustration by German Andino Woods.

Nevertheless, another force has taken over Melvin Clavel's old store. In the midst of so much confusion, and while Rivera Hernandez's gangs riddled the neighborhood with bullets, another silent house has steadily been taking over Sinai since mid-2013. This force is called Daniel Pacheco, and ever since he proclaimed his authority over Sinai, the gangs withdrew. Sinai has a new boss now.

Evangelical pastor Daniel Pacheco, in Rivera Hernandez. Illustration by German Andino Woods.

The six armies of Rivera Hernandez

"El Polache," followed close behind by "El Colocho" and "El Gato," leaves one of the houses with a metal gate. They look at us suspiciously and circle us. We are a strange group, perhaps the most exotic that has passed through these parts: a Salvadoran anthropologist and an artist from Tegucigalpa would probably go unnoticed anywhere else, but here we stick out like two martians.

The young men were really more puzzled than upset, and when they approached us, they fell silent, waiting for us to say something. We explained a little to them, but our explanation seemed to make little sense to them.

Very few foreigners are seen in the streets here and they observed us from head to toe. They were members of the MS13, and their mission is clear: to control the area and defend it from incursions by other gangs. Suddenly a lanky, dark-skinned young man appeared. They call him "El Calaca." His simple clothing contrasted with the power we knew he wielded. He is like a king of the slum, and he looked at us with perhaps even more curiosity than the others. He asked a few questions, and after talking we realized our answers sounded as though we came from a different world. This was when our guide, Daniel Pacheco, talked on our behalf. Everything was smoothed over and the young men invited us into their house.

Gang members' house in the Rivera Hernandez neighborhood. Illustration by German Andino Woods.

Daniel Pacheco is an evangelical paster and the son of a pastor. Everything in their family revolves around a small church, "Rosa de Saharon." In these neighborhoods, being a pastor has a different connotation than elsewhere in Honduras. In Rivera Hernandez, pastors are among the few people who command power, or respect, besides the gangs. Pastors are a type of "holy men" -- people go to them when they are in need of help, when they have no food to give their children, or when a gang has kidnapped a family member. The near total absence of the State, non-governmental organizations, and other institutions means these local pastors accumulate a significant amount of prestige and power. They are looked at as though they give off a divine aura.

There are many pastors, as well as small churches. There is one on almost every block. However, only a few pastors are truly venerated. The community is constantly scrutinizing them, pressuring them, molding them. A pastor cannot cheat on his wife, cannot have debts. Nor can he be seen smoking a cigarette in the corner store with other men from the neighborhood. Only those that follow these rules pass the test. Only then will the community bestow absolute trust upon them. These holy men usually pass on their status to their children, who begin their training in preaching and healing at an early age. Thus, small dynasties of pastors are created. Daniel Pacheco is the son and grandson of popular pastors and he is training his children the same way he was taught.

Within this small of group of holy men, Pacheco stands out for one thing: Daniel talks and negotiates with the six gangs that govern Rivera Hernandez.

Inside the house, the pastor reminded the MS13 gang members of the time he got them out of the police cell and talked on their behalf before the authorities. He also reminded them that he has known "Zuich" and "Stark" -- the MS13 generals in this area -- since they were young. The young men listened with respect. German took out a plate of chicken with rice that we bought in a Chinese restaurant on the block and he opened it in the middle of the group of gang members. They restrained themselves at first, like suspicious animals, but pastor encouraged them to eat.

“Eat, guys, take advantage! Just think about how many days you went hungry. Eat!”

After a little while, German hands over drawing and El Polache's eyes grow as big as dinner plates. He shows the drawing to the other gang members and, for a moment, while they pass the paper between them, they are like a group of kids chatting after school.

Pacheco told us that the gang members are virtually fasting. And he told us about the missions they carry out, about how the gang leadership barely gives them food to eat.

“These guys go hungry," the pastor said. “At times they have to be on watch all day without food. When I see them like that, I bring them a plate of food to share because I feel bad.”

Soon, the gang members started to warm up to us and started talking about the war against the other five gangs. They told us about what, according to them, was the betrayal of the Ponces and how the Maras exterminated them. Calaca pointed at someone and said without hesitation:

“He was a Ponce before. Now he belongs to the Marota,” he said, making the MS13 symbol with his hands. The man looked silently at the floor.

German took a notebook and a pencil out of his backpack and asked if he can draw them. Only El Polache said yes, but first he wrapped a red handkerchief around his face in order to protect his identity, like a bandit. German drew the first few lines and the gang members were silent. It was a touching moment. El Polache posed with his gangster face and his fingers forming the trademark Salvatrucha "claw," while German shaped him on the page. After a little while, German handed over the drawing and El Polache's eyes grew as big as dinner plates. He showed the drawing to the other gang members and, for a moment, while they passed the paper between them, they were like a group of kids chatting after school. But the moment was fleeting and they soon reverted back to their roles. "El Crimen," a young and scrawny youth, stopped shoveling down the rice and told us about how he survived seven gunshots, two stabbings, and five machete blows. The others told more anecdotes and the conversation drifted towards more thorny issues. Only El Polache was left looking at the version of himself in graphite and watercolor, staring so hard at the drawing it was as if he wanted to dive into it.

Later, our guide, Pastor Pacheco, signaled to me and German and told us that we could go into Barrio 18 territory, but we must do it carefully. According to Pastor Pacheco, the police chief responsible for this sector of Rivera Hernandez, and everyone else we've spoken with, this Barrio 18 faction is violent. They have earned their reputation through violence and are known for their rigid control of the community.

The pastor offered to bring us to Kitur, a sector in the heart of Barrio 18 territory. We left Sinai at 9:00 p.m. in Pastor Pacheco's truck, carrying musical instruments for an evangelical vigil. "El Malvado" the leader of the Barrio 18 faction in this area, told Pastor Pacheco over the phone that we needed to turn off all lights before entering the territory.

A soft rain erased the path before us and we had to guess where there were no potholes. Every time we passed a border that the gangs had marked with blood and bullets, Pastor Pacheco let us know. The rain grew stronger and the dirt streets of Rivera Hernandez were now small streams. No one was on the streets and only a few houses had their lights on. A malnourished horse wandered before us, sloshing water with its legs, the only way we could guess where the path leads.

Suddenly, a far-off light indicates which direction we should drive. We left the horse behind and followed the light shining from a hill. It was the Barrio 18's sign. The lights changed direction, and at the end of an alley a large group of shadows were waiting for us. Among them was El Malvado. He was wearing a button-down shirt, Nike Cortez shoes, loose pants and all the typical gear you'd expect from from a gang catalog. He was clean-shaven and wore a pair of sunglasses on his head, despite the darkness. A pistol hung from his belt and his hand gripped his cellphone as though it were an extension of his body.

El Malvado dominates various sectors of Rivera Hernandez, from Ciudad Planeta to Asentamientos Humanos and through Cerrito Lindo, where we were meeting him. He was surrounded by at least eight kids, most of them boys, who quickly lost interest in us and instead started calling the look-outs, or "banderas." None of the gang members were over 20 years old.

Malvado talked very little, and said canned phrases like, "The 18 are always pure, sincere and respectful." Later, he told us how he respects everything that comes from God. After a little small talk, he asked us to take him someplace else, and without waiting for an answer, El Malvado got into the front seat of our truck.

"Copy from the entrance below that I'm going to enter. Give a report," he instructed someone on his cell phone, while we once again began driving down a dirt path that was more like a pond at that point. We talked very little. He made a comment about how stressed he felt, being in charge of so many people. “It's like having a plane... if the pilot falls asleep, the plane crashes,” he said, holding his head.

Hardly a minute went by without El Malvado making or answering a phone call. “Mmm.. stop a white car that's heading for the red light. That's not a local,” he said into his phone.

The tour was coming to an end. We left him in the same place we picked him up, and there he met with his second-in-command. Both went into the shadows, but not before telling us that we could drive their territory without worrying, since they had already alerted all the Barrio 18 members in Rivera Hernandez of our presence.

The next morning there was bad news for El Malvado and his gang. The police had captured four of their members and had them in custody at the police station. Outside, a group of weeping women were waiting. One of them cried, “If I had only sent him to buy me dough, he would be in the house right now.”

A police officer approached and reprimanded them. He told them that it was their fault that the kids were gang members. He told them that while arresting the kids, one of them said, "This is what we are, this is our fate as gang members.”

The mother of the gang member who said this began to cry. The father said, "That is what he said...? Then that idiot can go ahead and die. I have already done so much for him, let the fool die!”

The man then went to the police officer and told him about how day after day, he beat his son, but despite this the boy remained "on wrong path."

"This fool, you see, I have beaten him, I have beaten him. In order to straighten him out, but he doesn't want to understand.”

Eventually, the boys who were arrested left the police station. They were four boys. All of them were younger than 17. All of them lowered their gazes when they saw their mothers. The biggest of all of them tried to calm the women and said defiantly, "Calm down, this is not the end of the world! We are going to resolve this."

But he looked down when his own mother approached and began to reproach him. “Very nice, Marlon, very nice, how the hell are you going to get out of this one? This time I'm not going to help you,” the woman said, mumbling some curse words to herself. She looked sharply at her son, who had already lowered his eyes to hide them from the woman's anger.

The gang member who told the police, "This is our fate" was just a boy. He was 14 years old, but he looks younger. He was dark-skinned and had large, light-colored eyes. His clothes were very simple, the same as his mother's and father's. This boy was not afraid. He had a smile on his face and even appeared to be lapping up the attention.

Then the boys were herded into a police vehicle, to be taken down to a courthouse in San Pedro Sula. Before leaving, most of the boys lost their tough-guy composure. They began calling out for their mothers and bitterly crying together. One of the boys did not stop crying until we lost sight of him. His mother sat down on the sidewalk with her hands over her face, repeating again and again: "My boy... my boy, my boy, my little boy." The sister of the youngest boy walked behind the truck and said to her brother: "When you get there, close your mother up, do you hear?" and she put a finger to her lips.

The boys were accused of carrying an illegal weapon, drug trafficking and carrying ill-gotten money. We asked El Malvado about the arrests, but he told us there was no problem, that they were all "banderas," the lowest-ranking members of the gang hierarchy.

Later on, we visited El Malvado's enemies. We went to the boundaries of Sinai and waited there for the MS13. They were happy because a boy who they thought was going to die had left the hospital. They called him "Bocha," and in fact, his name had already been graffitied onto a wall, as a type of obituary. According to gang protocol, seeing someone's name on this wall is like seeing it on a tombstone. We spend the afternoon with the MS13 in their territory, eating Chinese food and swapping stories. After a while, El Calaca explained that we had to leave, since they were at war and could not be so careless. But before we left, he ran into his house and brought out a black handkerchief. He put it on like a thief from the Wild West would and asked German to draw him. He stood in front of the wooden door of a nearby house and posed with his hands making the unmistakable Salvatrucha claw.

Meanwhile, Bocha ate slowly and looked at German and Calaca with a zombie-like expression. His chest was wrapped in bandages; the doctors in the public hospital left him with a large, vertical scar. Suffice to say, they didn't think of aesthetics when they stitched him up. Bocha had been shot by El Malvado's people for entering their territory. Bocha was unarmed and managed to run to the nearest police station, where the officers reluctantly mounted him on a stretcher and brought him to the hospital. Investigating the incident appears to not be an option. “I saw those assholes and the next time they will see...” Bocha said, between breaths, as loud as his feeble voice permitted.

Bocha, an MS13 gang member in San Pedro Sula. Illustration by German Andino Woods.

Everyone then headed off towards the bowels of the neighborhood. Only El Calaca returned and reminded German to give him the portrait, once it was done. But El Calaca never ended up seeing it: he was killed weeks later. Bocha was also unable to carry out his revenge, since he was killed by the Barrio 18 days after Calaca's death.

The house. Rivera Hernandez neighborhood, San Pedro Sula. 2015.

Melvin Clavel's house now looks different. At least on the outside. Pastor Daniel Pacheco, using what little salary he earns as as a carpenter, was able to buy paint and, along with the young children from his church, painted the house one Sunday afternoon. One of the walls depicts what's supposed to be Roman gladiator, if you look at it with enough imagination, and acknowledge that the artist has no idea how a Roman gladiator should dress. The gladiator was painted by "the best artist in the neighborhood," who is actually a drunk. They say this man went crazy after handling too much paint solvent, and that he began sniffing it instead of painting. The man spent some time working on the gladiator, then sniffed solvent all afternoon. That's why it took a few days before the gladiator was finished.

Inside the house, Pastor Pacheco's volunteers washed away Melvin's blood stains. The pastor and his team took out the trash, planted flowers, and threw away everything that one would expect to find a gang hideout: empty liquor bottles, cigarette containers, torn women's clothing, and rusty machetes. The pastor also built a large sink that the children from the neighborhood use as a pool. At night the community hosts small soccer matches, and on Sundays they hang piñatas and organize games for the children. Other days the house is filled with evangelicals and their singing. It is the closest thing that Sinai has ever had to a neighborhood center-- something that is normal elsewhere, but not here. It is an oasis of peace in Rivera Hernandez.

Those who live in Rivera Hernandez will invite you into their homes if they catch you taking a peek inside. Despite all the violence, the people seem trusting. You only need to ask a simple question to get them talking with strangers all afternoon. They will tell you their life story and that of their siblings and cousins.

The people of Rivera Hernandez are happy, and when the afternoon comes to an end, groups of people will congregate on corners just like in any other neighborhood. They talk and laugh loudly. If they want to say yes, they say "check" ("cheque"), and, if they are upset, they say they feel "ruined" ("maleados"). They talk quickly and with a Caribbean accent that reminds one of the coast. These people will offer food and blankets to strangers, even though they know they are offering all that they have.

There is no regular State presence here, only an occasional police or military patrol, which usually only comes during a fumigation campaign against mosquitoes carrying chikungunya or to inspect the gang-infested schools.

The violence here is difficult to understand. It is so present in everything, so immersed in everyday life, that it is difficult to decipher. The people live with the violence without thinking about it, like how the Eskimos spend their days without thinking about the snow that surrounds them. This is life in Rivera Hernandez, the poorest neighborhood in San Pedro Sula.

Fuente: http://www.insightcrime.org/investigations/gang-history-rivera-hernandez-honduras

Reporte completo en español en PDF: http://www.insightcrime.org/images/PDFs/2015/MarasHonduras.pdf

belze- Staff

-

Cantidad de envíos : 6135

Cantidad de envíos : 6135

Fecha de inscripción : 10/09/2012

Temas similares

Temas similares» Autor de tiroteo en Fort Hood, Texas, se suicidó tras dejar 3 muertos y 16 heridos; sirvió en c

» Será acusado Nidal Malik Hasan, el atacante de Fuerte Hood de asesinato premeditado.

» Most important war in Mexican history

» Mexican Aviation History

» Mexico y Cultura

» Será acusado Nidal Malik Hasan, el atacante de Fuerte Hood de asesinato premeditado.

» Most important war in Mexican history

» Mexican Aviation History

» Mexico y Cultura

Página 1 de 1.

Permisos de este foro:

No puedes responder a temas en este foro.

Índice

Índice Últimas imágenes

Últimas imágenes Registrarse

Registrarse Conectarse

Conectarse